Rough and Chile

- Details

- Published on Sunday, 27 August 2006 12:11

- Written by John Holborow

I am probably not the only fisherman who spends an indecent amount of time reading about fishing, and perhaps not the only one to have a weakness for what my wife refers to as “fishing porn” - glossy brochures and websites extolling the virtues of luxury fishing lodges in exotic locations.

I am probably not the only fisherman who spends an indecent amount of time reading about fishing, and perhaps not the only one to have a weakness for what my wife refers to as “fishing porn” - glossy brochures and websites extolling the virtues of luxury fishing lodges in exotic locations.

They tend to feature colourful photos of wealthier men than I, holding aloft spectacular catches, beaming at the camera. To extend the analogy, it is a form of self-abuse to read such “literature” because the price tag means these kinds of trips are way out of my reach. Several thousand US dollars a week, before international flights tends to be the bare minimum - whether you are looking at Alaska, the Kola peninsula, the Bahamas or Patagonia, it seems to make little difference. I resigned myself to waiting for that lottery win.

But then, a few years ago, I found myself with a lot of unused holiday to burn, which when combined with the Christmas break and moderate amount of groveling would give me five full weeks in which I could travel. One wet October afternoon I bought myself a bargain ticket to Santiago in Chile - it helps to be prepared to endure lengthy stopovers in Madrid or Miami where flights to South America are significantly cheaper. I also secured a special roaming deal with domestic airline Lan Chile, and then scratched my head and wondered exactly what I was going to do when I got there.

The guidebooks were not much help beyond a few references to the availability of guides in adventure sports hubs like Cohaique. My online research (work took a bit of a back seat that autumn) seemed to indicate that the only option was to stay in a lodge and pay through the nose. Still, everything I read told me this was an amazing place to visit and I was sure I would find a way to cast a fly somewhere or other. I did discover one important thing - in Argentina and Chile property law means that no fishing is actually private though access can be privately controlled. But there was no information for the independent fisherman, let alone any indication that there was out there somewhere a Patagonian cousin of Bruce Sandison’s extraordinary guide to Scottish waters.

My first stop, after a couple of days in Santiago, was the small town of Villarica, across its namesake lake from the ski resort of Pucon, and under the impressive shadow of the snow-capped Villarica volcano, which, my guidebook cheerfully told me, would inevitably wipe both towns off the map at some point in the not too distant future.

I secured my fishing permit from a government office where I confirmed just how few Chileans outside the capital speak English. Each region has its own permit, but there is a national permit for visitors. In a hardware shop in town I found some dusty ‘Mosca’ for sale - pheasant tails, elk hair caddis and rubber legged nymphs - along with a larger arsenal of spoons and rapalas. My Spanish was not up to much in the way of a discussion of tactics, but I did get pointed in the direction of the ‘barcos’ (boats) pulled up on a sandy beach a few minutes walk out of town. For US$30 I secured the services of Pablo - a taciturn boatman, a seat in his fine wooden boat, and a car and trailer to pick us up that evening at a prearranged spot downstream. The Rio Tolten is a substantial affair - fifty yards wide where it leaves the lake. Pablo cast a critical and none too impressed eye over the contents of my fly-box. He pointed to a teal and silver, which I tied on and flicked out in the direction of a likely looking riffle. The fly was in the water for a second or two, whipped fast downstream by the powerful current when a savage tug indicated I was connected to my first South American trucha. It was probably half a pound in weight, a bright silver rainbow, but like no rainbow trout I had ever seen at home – big clean fins, a slim torpedo body, a sprinkling of tiny ink black spots. Pablo looked unimpressed while I grinned and jabbered excitedly in bad Spanish. More fish came as the river swept us on through huge bends under crumbling banks. Now and then there were islands, fallen trees, and occasionally streams joined the river emerging from the thick vegetation covering the slopes of the valley. There was little or no sign of human activity. Pablo offered no advice at all, and I just tried to guess where the fish might be. Mostly they were there. In fact mostly they were everywhere. I lost the teal and silver in a low hanging branch and opened another fly box. Pablo sucked on his cigarette and looked over my shoulder. He jabbed a finger at the dangling rubber legs of one of the nymphs I had bought that afternoon.

Trout in Patagonia were, as in New Zealand, introduced in the nineteenth century and they have taken to their new home with considerable gusto. Rainbows, browns and brook trout all thrive on both sides of the Andes. That first afternoon on the Tolten I caught an indecent number of those immigrant rainbows, and every five minutes I said a prayer of thanks to the men who had brought those first fingerlings to these rivers. They may not have been native, but these were wild fish. There is no restocking in these waters. The biggest was not much more than a pound, the smallest less than half that size. But with the help of the powerful current they fought like fish twice or thrice their size, and I was taken down to my backing on a couple of occasions. Yes, it was all too easy, and no, none of them were the trophies from the brochures; I was blind-fishing turbid depths, not stalking in gin clear shallows; my guide did not tie my flies on for me, or stealthily ease me into position to cast for a brooding speckled leviathan, instead without asking he dispatched a few of the fish with a flick of his wrist, and put them in a bag to take home for his tea; nor did he barbecue my lunch and offer me a glass of chilled chardonnay - he chain smoked and looked rather bored; and at the end of the day my accommodation was not charming and rustic - it was downright dingy with no hot water and nylon sheets. It was not the sort of fishing I would want to do day after day, but nothing could change the fact that I was fly fishing in Patagonia on a budget and catching fish.

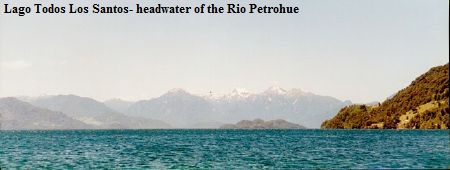

After a successful start to my Chilean trip, and feeling extremely optimistic, I headed south to Puerto Montt, a bustling coastal town where there is plenty of cheap accommodation, and as there is everywhere in Chile, fabulous seafood. My plan was to explore some of the rivers and lakes inland while waiting for a flight to Chaiten on the banks of the famous Lago Yelcho, one of Chilean Patagonia’s premier fly-fishing locations. I hired a car in Puerto Montt and fished the beautiful Rio Petrohue, and some of its smaller tributaries. Access was difficult and haphazard: I asked at farms if I could cross land, and kept a case of Concha Y Toro Merlot in the boot of the car to ease negotiations. But there was no escaping the fact that the river was best fished from a boat, but I did not have one and nor were there any to hire by the day. The banks were crowded with almost impenetrable undergrowth. I found a few good spots and hooked my first Chileno brown trout - a bruising twenty-inch fish, which broke both my leader and my heart as it came to the net. I had more luck on the lakes and had good evening sport casting dry flies to rising fish in quiet sandy bays on Lago Llanquihue. But mostly I spent a lot of time trudging up blind alleys.

At Puerto Montt airport I came across a party of American fly fishermen who had also been fishing the Petrohue, and like me were headed for Lago Yelcho. They had spent the days drifting on rafts helmed by experienced guides, casting to big trout, and doubtless would do much the same on Yelcho. They were politely sympathetic and did not need me to tell them that without expert and expensive assistance the Petrohue was nigh on impossible to fish. They had all had trophy fish in their three days and suddenly I was a little less comforted by the thought that they had paid thousands of dollars, and just felt plain jealous. I wondered if the basic pleasures of the Tolten would be the exception to the rule, and started to fear that the very good reason why people paid the money was because the alternative was not to get to fish much.

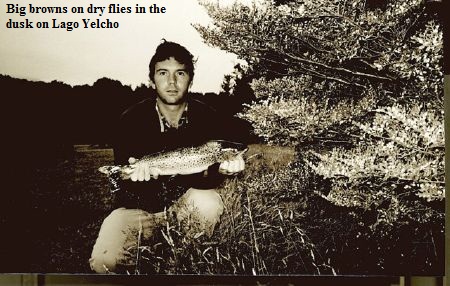

Arriving in Chaiten after a genuinely terrifying flight, I found a cheap room at a hospedaje: a licensed way of staying with a local family - a common system in Chile and one that I can heartily recommend. The Chilenos I met were tirelessly polite, warm and generous people. The idea that someone would come to their country to catch “trucha” and insist on doing so “solo con mosca” was clearly baffling to many of them. But they were happy to help me try and find good fishing whenever they could, and I was rapidly introduced to many of the farmers with land around Lago Yelcho, and the many streams running into it. I would rise at 3am; hitch a lift, if there was anything on the road, and head out to one of several spots I identified around the lake. Some of the best fishing was to be had amongst the reeds, roots and sunken forests on the south end of the lake. A nightmarish place to try and land a fish, and I lost five for every one that came to the net. These were mostly Trucha Café, dark backed browns, and they loved dry flies and orange-bodied daddies in particular. A float tube would have been incredibly useful here. As it was I developed a half wading, half swimming technique, which did not do much for my camera and left me facing some sodden walks home along dusty unmetalled roads.

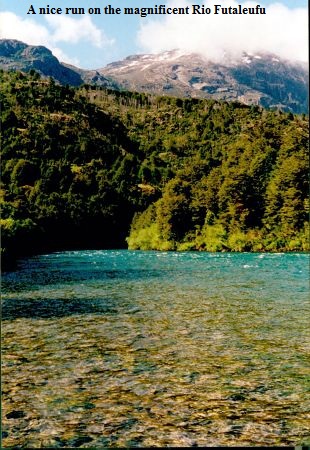

The biggest river that drains into Lago Yelcho is the Futaleufu, which begins its life in Argentina, passes close by the Chileno border town bearing its name, and then swings south through a spectacular gorge, which attracts white water adventurers from all over the world. It looked like it would be terrifying in a canoe, but it is certainly an incredible place to fish. Several luxury lodges put their guests on the Futaleufu, but the shoestring fisherman prepared to walk, camp and ask politely will find he can get on most of the best water. Access is never easy - the banks are dense with thorn, bamboo, and fuchsias. Wading is challenging often simply because the river is so powerful. It is also very cold. Repeated immersions on my first day made me wary of ever wading beyond thigh deep, and I was glad of my neoprene waders even though it was in the high nineties. In the upper valley, high enough that it was only occupied in summer months, I found a farmer who would let me sleep in his barn, and wander his land for a contribution towards overheads (ten dollars a day). A week passed in a wonderful daze of early starts, long exhausted siestas and frantic evenings with mosquitoes devouring me as I tried to tie on a fly in failing light for one last cast. The trout I caught - a good mix of rainbows and browns averaged a pound and a half. There is no doubt that staying at a luxury lodge and fishing with an expert guide from a boat I would have caught bigger fish. I might well have had a more comfortable bed with fewer fleas in it. I might even have had more than the two small bottles of beer a day I had been able to carry in. But I cannot imagine how I could possibly have been any happier. Images from that week are carved into my brain - the trout I took which raced another much larger fish to my fly and sadly won; watching the morning sun burn the mist off the river; the big brown who finned the waters just below the farm and ignored the contents of my fly-box until finally I persuaded him to take a tiny pheasant tail nymph tied on a foot of nylon to the bend of a big bushy dry fly; falling asleep in the shade of a beech tree with a couple of fish on the bank to put a smile on my host’s face at supper time; and above all that extraordinary river, ever-rushing, a great swift gliding expanse of icy clear water that always threatened to pick you up with it and sweep you away.

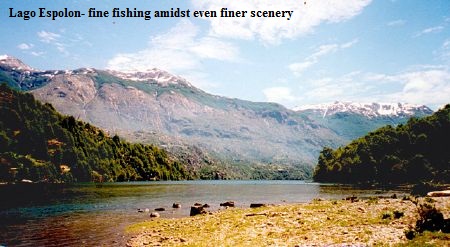

I fished other extraordinarily beautiful wild waters using the town of Futaleufu as my base. I overcame a lifelong terror of all things equine and hired a horse to take me up to Lago Las Rosas - the quintessential high Andes lake. Once there I missed the only fish I rose all day and caught nothing, but would happily go back there again and again, if only just to spend a day surrounded by snow-capped peaks. I hitchhiked and hiked to Lago Espolon and caught countless breakfast fish on a Humpy Dry Adams while getting dreadfully sun burnt. And I went back to Chaiten and fished Yelcho one last time in the company of a mad German with a home made float tube. There is a lifetime’s fishing in the rivers and lakes in this region and with some not inconsiderable effort, and polite requests made at remote farms, the independent traveller can fish to his heart’s content.

The final chapter of my budget assault on the trout of Chile took me to the tip of the tapering continent - the Magellan’s and Tierra del Fuego. My base was Punta Arenas - a windy port with the slightly unhinged feel of a frontier town. As soon as I arrived I blew most of the rest of my cash on the hire of a four-wheel drive pick up truck and began to explore. The trout fishing in Tierra del Fuego probably needs no introduction - it is here that John Goodall, hallowed be his name, introduced Scottish brown trout stock into the rivers on his enormous Menendez sheep ranch, most notably the Rio Grande. And, as my great aunt and someone else on TV used to say, didn’t they do well. Many of the descendants of those fingerlings run to sea now, and return as the most spectacular sea trout in the world. Here, on both sides of Tierra del Fuego’s still disputed border are found the most exclusive fishing lodges in South America. But the same rules apply - no one can own the riverbank below the high water mark, so in theory anyone can fish the rivers. Unsurprisingly the commercial enterprises charging people £4000 a week to fish there are not altogether enthusiastic in welcoming passing fishermen dropping in to fling a weighted Chartreuse streamer into the undercut of one of the Rio Grande’s huge sweeping bends. I had a few hand drawn maps of circuitous routes, which I hoped might allow me access to the famous Rio Grande.

As it turned out it was the police who ran me out of Argentine Tierra del Fuego. The hire car company had filled out the forms incorrectly and I found myself accompanied by a man with a rifle to meet ‘El jefe’ at Police HQ in the township of Rio Grande. He was very polite - Las Malvinas were not mentioned once - but immoveable. I was sent back to Punta Arenas - some six hours driving on appalling unmetalled, truck rutted roads, not to mention a ferry ride across the Magellan strait. There are as far as I can tell about three petrol stations in T del F and it is therefore essential to have the back up of a ‘bidon’ (jerry can). It is also essential to remember to fill it up. I lost an entire day through this oversight - a long, hungry day spent hitching rides and lugging a leaking bidon, and swearing a lot.

There is no other landmass on the same latitude as the Magellan’s and Tierra del Fuego. The wind whips around the globe without any obstacles to take the sting out of it; that is when it’s not tearing up in an icy blast from the Antarctic. This is what levers up fifty-foot swells and makes nearby Cape Horn quite such a terrifying experience for sailors. It also makes walking down the street in Punta Arenas an experience akin to having your face shot blasted. Hint for contact lens wearers: don’t. There are few trees, and the wildlife - penguins, guanacos, foxes, and the emu-like flightless rhea - all seem to spend their lives hunched with their backs to the wind, looking forlorn. The fishermen do the same.

When I had finally got some petrol back in the tank, and acquired the proper paperwork, I slept well on the bench seat of the pick up. I had parked up down a back road near Lago Blanco, the headwater of the Rio Grande, on the Chileno side of the border. I peered out of fogged up windows and saw some guanacos – particularly hirsute cousins of llamas -

gathered nearby looking miserable in the drizzle. I got out of the truck thinking I might have a few casts on the lake before heading back across the border to have another crack at the Rio Grande. The wind simply knocked me flat onto my backside. Not a gust of wind - just a constant roaring gale. They call it La Escoba del Dios - God’s Broom - and words cannot really do justice to its relentless ferocity. The waves on freshwater Lago Blanco would have been considered very decent surf on a winter’s day in Cornwall. Somehow I got a line out on a small stream running into the lake and caught the one and only brook trout I have ever caught - a beautiful creature of a pound or so, which I cooked on my stove for supper. Like all char it was delicious.

Back in Argentina I followed the maps, found a most promising looking stretch of the Rio Grande and set up my nine weight rod for the first time on this trip. This would be my first time casting with the T-400 Teeny line - a shooting head that sinks like a stone. In the roaring wind casting anything involved an act of faith, and a resigned acceptance that at some point the law of averages said a size six hook was going to bury itself into one ear or the other. The shooting head helped a lot - eliminating the need to false cast. Delicate presentation this was not. Several hours of hard work later I had nothing to show for my efforts except for an appreciation for Mr Teeny’s line designing skills. But I had heard an almighty splash upstream of me – and it had to be a beast to make itself heard over the howling gale. But I had to accept that the main runs of sea run browns were at least a month away and I was frittering away limited time in a somewhat desperate throw of the dice.

So I retreated to Chile vowing to return another year. My sources told me of smaller streams to the south of the Rio Grande where a budget fisherman can - timing his arrival better than I did - have a real crack at double figure sea trout in this extraordinary wilderness. For the time being I had to settle for something more in keeping with the more modest results of my trip.

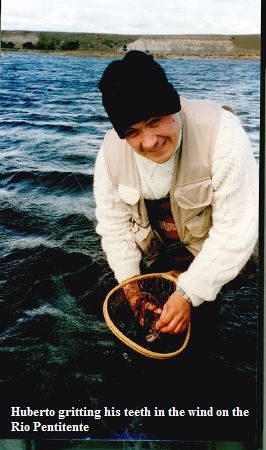

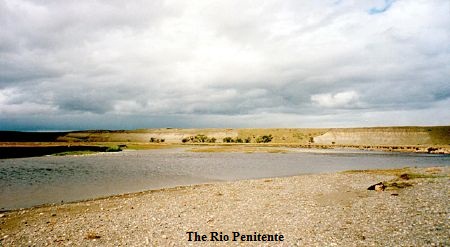

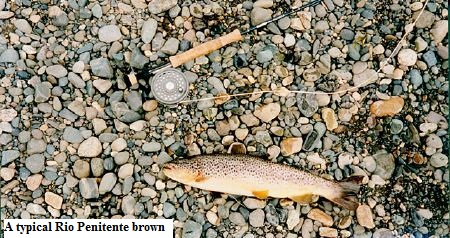

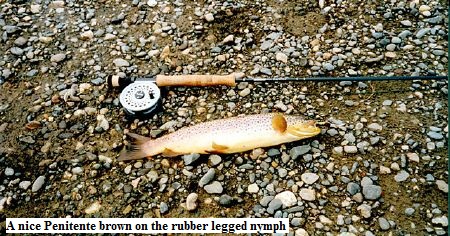

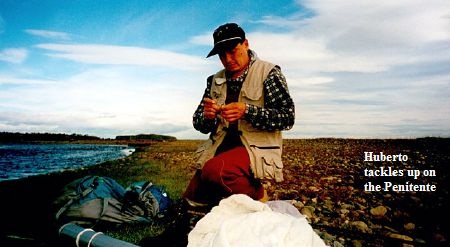

This turned out to be the Rio Penitente - a piece of water that I hold in as great affection as the Futaleufu, the Orchy and a couple of hill lochs whose exact location I try to be vague about in conversation. Reluctantly, with time running out, I turned to a tactic I had used while fishing the week before around Cohaique, and forked out for my third guided day in Chile. Then I set off at crack of dawn with the wonderfully cheerful Huberto. He thought it hilarious that I was sleeping in a hire car, but was enough of a trout fanatic to understand why. He took me to a stretch of the Penitente, a river draining the world famous catchments of the Torres del Paine, which was like a junior version of the Rio Grande. There was not a standing tree in sight, nor another human being or sign of one. The river had carved deeply under sandy banks. The wind pressed every blade of vegetation flat down against the gritty soil. It was fishing with the shooting head again, and using rubber legged nymphs - not the sort of fishing that many people think of when they think of the gentle art of fly-fishing for wild trout. But for me at least it was the essence of a fishing challenge, requiring a bit of skill and a lot of determination, and every now and then offering up spectacular excitement. A constant howling wind like that saps your strength. Casting a heavy line like that is tough on the wrist. To give you an idea of how bad the wind was, I kept thinking about giving up, and going and having a beer with Huberto. But then I would time a strike right and lift into a solid, fat trucha café. I caught fish up to two, maybe two and a half pounds; maybe a dozen in six hours. They fought with a range of tactics - sullen, deep, head shaking, followed by searing runs like no other browns I have caught. They had deep bellies, coffee coloured flanks and a big blue thumbprint sized spot on their gill covers. I returned the next day alone, and the day after that. My sun burnt skin peeled off in the scouring wind; my hands cracked and my lips were raw. I cast until my arm throbbed. I wrapped my head with a scarf. I walked and I fished. I started to understand where the better fish lay, and I became better at recognising what was a take - an almost imperceptible deviation in line - and what was just an effect of the complex currents and wind. With a few hours left before my flight, and most of that needed for the drive to the airport, I was still there on the Penitente. Quite suddenly the wind just stopped. The silence was deafening. I actually looked over my shoulder because it felt like a windbreak had been erected behind me. The river was transformed. Fish were rising - perhaps they had been all along, but now the surface was a flat calm I could see their rises and here and there I could see the fish themselves. With urgent fumbling hands, expecting the gale to resume any moment, I switched spools to a floating line, tied on an elk hair caddis and launched it out towards the spreading rings of the last rise. Third cast produced a slashing, violent take - and a miss. Moving on I missed another and then spotted and hit one, two, and finally three beautiful plump brown trout. The same class of fish I had been catching the last few days but somehow amongst the most satisfying fish I have ever hooked. I needed to leave but kept on fishing, working my way back towards the road, telling myself each cast was the last one. The last fish I caught in Chile was the biggest fish I had caught in my stay. I measured it against my rod and later confirmed that it was 25 inches from its slightly hooked jaw to its oversized tail. A magnificent fish, probably sea run, and I can still feel the solid weight of it in my hands as I released it.

There is no doubt that the independent fisherman will miss out on many of the opportunities, not to mention comforts, that deluxe professionally run fishing lodges have to offer, and I would be the last person to turn down the chance to spend time at such a place. There’s no substitute for local knowledge - as many a blank day have taught me - and that is part of what your money buys you, along with uncomplicated access to the water. Local guides, hired by the day, are a good halfway house, and will give an idea of how to access some water, saving a lot of time, and there’s nothing to stop you using a day with a guide as a reconnaissance trip for some solitary exploration. The Chilenos are wonderful, welcoming people, and they are justifiably immensely proud of their country; they will generally welcome polite requests to cross their land, but that generosity should never be taken for granted in Chile or, for that matter, anywhere.

There is no doubt that the independent fisherman will miss out on many of the opportunities, not to mention comforts, that deluxe professionally run fishing lodges have to offer, and I would be the last person to turn down the chance to spend time at such a place. There’s no substitute for local knowledge - as many a blank day have taught me - and that is part of what your money buys you, along with uncomplicated access to the water. Local guides, hired by the day, are a good halfway house, and will give an idea of how to access some water, saving a lot of time, and there’s nothing to stop you using a day with a guide as a reconnaissance trip for some solitary exploration. The Chilenos are wonderful, welcoming people, and they are justifiably immensely proud of their country; they will generally welcome polite requests to cross their land, but that generosity should never be taken for granted in Chile or, for that matter, anywhere.

I am not ashamed to admit I fell in love with Chile. The fishing was magnificent, and occasionally the catching was pretty good too. And for those like me who appreciate spectacular scenery, the simple pleasures of a campfire at the end of a long day walking and fishing, and the excitement of not knowing quite what the next cast will bring, I cannot think of many better places to go to escape the British winter.

John Holborow lives in London with his wife Sophie and two year old son Mani. In the past twenty years he has travelled in Europe, the Caribbean, the Pacific Islands, South and North America in a largely unsuccessful pursuit of fish, and these days can often be found scaring the trout on the River Itchen in Hampshire. But his fishing heart remains in the land where he spent much of his childhood and he would choose a day on a remote Scottish hill loch ahead of anything else.