European Unions

- Details

- Published on Sunday, 06 April 2008 06:23

- Written by Bruce Sandison

Matters European are rarely off front-pages or television news these days. Politicians go at it hammer and tongs, banging away endlessly about Euros, the common agriculture policy, or lack of it, and how we must all learn to snuggle up together, or not, depending upon your point of view. I don’t know how I will cast my vote if a referendum ever comes, but I do know we have to accept that people are different.

Matters European are rarely off front-pages or television news these days. Politicians go at it hammer and tongs, banging away endlessly about Euros, the common agriculture policy, or lack of it, and how we must all learn to snuggle up together, or not, depending upon your point of view. I don’t know how I will cast my vote if a referendum ever comes, but I do know we have to accept that people are different.

This was exemplified to me when I spent a week fishing in the company of two Spaniards, two Germans and two French anglers. They represented three European fishing magazines, Der Flegenfischer, La Peche and Trofeo, a journalist and photographer from each. I arranged the visit and acted as their host and guide. The week was illuminating, incident-packed and great fun precisely because of their different national characteristics.

The Frenchmen arrived minus their fishing rods and half their luggage. A not unusual Inverness airport occurrence in my experience. Apparently, the missing baggage was on its way to Rome. They were less than pleased and expressed this displeasure, loudly, to the duty staff at the BA desk. After a lot of Gallic shrugging and Gauloises the problem was resolved. I would lend them tackle until theirs could be located and returned.

The Germans, however, had everything neatly to hand, plus collapsible mini-trolleys for the transportation thereof. They checked their baggage, heel-clicked hello, then marched purposefully and in good order to where the car was parked. Here, everything was meticulously checked again prior to being loaded into the boot. I was impressed.

On the other hand, the Spaniards, who were accompanied by their wives, wandered round the airport for half an hour, buying souvenirs, smiling, cheerful and carefree. By the time I had them all gaggled and loaded and ready for the off, my German and French friends were distinctly edgy.

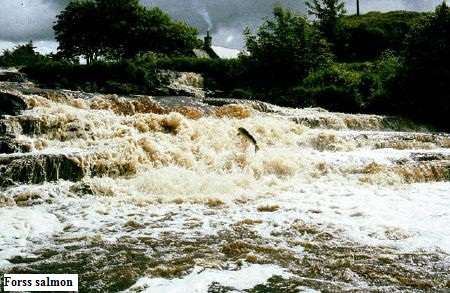

We spent our first day together salmon fishing on a north-west Sutherland stream. The water level was perfect and fish were showing almost continuously. By lunchtime there were four fresh-run salmon on the bank: two to the Germans and two to the Spaniards. My French companions said nothing, but they were seriously glum. I sensed an international incident brewing. Happily, the afternoon proved to be kind to the French, albeit with only one fish between them. But honour had been satisfied.

I had asked them to be back at the car for 5.30 pm, leaving plenty of time to relax and freshen up before dinner. As I waited patiently to collect my little flock, I watched them coming down the riverbank. The track they had to follow divided just before a fishing hut. One branch, the correct route home, angled away from the river, round a small hillock to a bridge across the stream. The other branch led to a dead end and a precipitous drop into a deep pool.

At 5.25pm the Germans hove into view, their fish slung on designer ropes fitted with wooden carrying handles. At the junction they unhesitatingly followed the correct path and arrived at my side at 5.30pm precisely. At 5.45pm, the Spaniards appeared, talking earnestly together; looking at the river, pausing to inspect pools and to point at splashing salmon. Their fish were slung casually over their backs. At the junction, they started down the wrong track, then, realising their mistake, they retraced their steps and rounded the hillock.

At 5.25pm the Germans hove into view, their fish slung on designer ropes fitted with wooden carrying handles. At the junction they unhesitatingly followed the correct path and arrived at my side at 5.30pm precisely. At 5.45pm, the Spaniards appeared, talking earnestly together; looking at the river, pausing to inspect pools and to point at splashing salmon. Their fish were slung casually over their backs. At the junction, they started down the wrong track, then, realising their mistake, they retraced their steps and rounded the hillock.

By 6.00pm the Frenchmen had yet to appear and the Germans were agitated, worrying about dinner. “We must go. We will be late. Leave them a note saying you will come back for them.” We heard the late Frenchmen before we saw them when they were some distance off, talking at the top of their voices. Then we saw them, gesticulating down he track, arms flying, the air blue with tobacco smoke. Without pause they took the wrong turning and arrived at the side of the river.

Their salmon fell to the ground, almost into the stream. After a heated argument about what to do next, they walked back to the junction and continued the debate over another cigarette. I roared across the river and waved directions. Eventually they found the route and tramped over the bridge to where we were waiting, full of courteous apologies for being late. “It is so beautiful” they said, “we just forgot about the time.” I walked back across the river to retrieve their salmon, which, in the white heat of argument, they had forgotten to pick up.

There were language difficulties, mostly on my part, but between us we managed. The Germans spoke reasonable English and French. The Spaniards had good English and some French and the French spoke excellent English and German. However, one thing we all had in common was a love of fishing and that joy solved most problems.

Which I suppose is what makes fishing such an international blessing? Regardless of race, class, colour or creed, or language spoken, most anglers identify with similar things: a shared concern for the environment and for the well being and future of our well-loved quarry, be it salmon, trout or sea-trout.

At dinner on the last night, the Germans, by way of a “thank you” gave me a book. For the first time since leaving home I reached for my spectacles. I put them on a gasped in fright. I had suddenly gone blind in one eye. Then I remembered my son and daughter being particularly solicitous before I left: “Here, dad, you almost forget your glasses”. The blighters had pasted a black patch over the port lens.

I peeled off the patch, much to the amusement of the assembled company and grabbed the cloth from inside the case to wipe the lens clean. As I did so, I exposed a neatly printed note, stuck firmly in place, upon which was written Basil Fawlty’s classic line: “Don’t mention the war!” Maybe if our political leaders spent more time fishing and less time gabbing, they would get on better and perhaps make the world a happier place?

Bruce Sandison is a writer and journalist and author of nine books, including the definite anglers' guide, 'The Rivers and Lochs of Scotland' which is being revised and updated prior to republishing.

He contributed to 'Trout & Salmon' for 25 years and was angling correspondent for 'The Scotsman' for 20 years. Sandison writes for the magazine 'Fly Fishing and Fly Tying' and provides a weekly angling column in the 'Aberdeen Press & Journal'.

His work, on angling, Scottish history and environmental subjects, has appeared in most UK national papers, including 'The Sunday Times', 'The Telegraph', 'The Daily Mail', 'The Herald', 'Private Eye', 'The Field' and in a number of USA publications.

Sandison has worked extensively on BBC Radio. His series 'Tales of the Loch' ran for 5 years on Radio Scotland and was also broadcast on BBC Radio 4 and on BBC World Service. His series, 'The Sporting Gentleman's Gentleman' and his programme 'The River of a Thousand Tears', about Strathnaver, established his reputation as a broadcaster.

Sandison has had extensive coverage on television. He wrote and presented two series for the BBC TV Landward programme and has given a number of interviews over the years on factory-forestry, peat extraction, wild fish conservation and fish farming.

Sandison is founding chairman of 'The Salmon Farm Protest Group', an organisation that campaigns for the removal of fish farms from Scottish coastal and freshwater lochs where disease and pollution from these farms is driving wild salmonid populations to extinction.

Bruce Sandison won 'Feature Writer of the Year' in the Highlands and Islands Press Awards in 2000 and in 2002, and was highly commended in 2005. Bruce lives near Tongue in Sutherland with his wife Ann.