Last Tangle In Harris

- Details

- Published on Monday, 26 June 2006 17:31

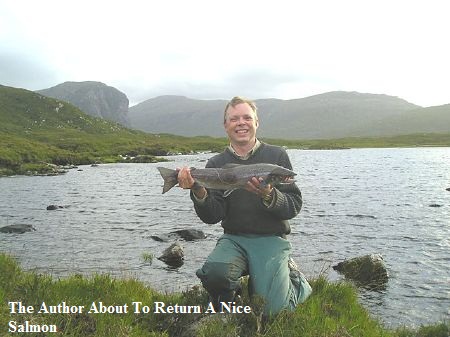

- Written by Alan McGowan

A STARTLED stag downwind of the watershed turns and bounds away as you breast the mountainous ridge. That's how you remember it a few days later, back safely in front of a glowing peat fire.

A STARTLED stag downwind of the watershed turns and bounds away as you breast the mountainous ridge. That's how you remember it a few days later, back safely in front of a glowing peat fire.

In reality, you clamber over the ridge, wipe sweat from your blurring vision, stagger upright, face the cooling wind and repeatedly gulp air as you try to stop lapsing into unconsciousness.

You're halfway there.

Before you in the valley below meanders a very ancient river whose heathery banks you'll be tackling up beside within an hour. From now on it's pretty much an involuntary descent from the ridge to river, an inelegant freefall hundreds of feet to your fishing destination in this remotest of prehistoric corners on the hauntingly-beautiful Isle of Harris.

Three miles from the sea the little river widens to two large spreadings; lochs in their own right on the map. And it's here that the trout rod you hauled up and over the mountain in its protective tube will hopefully bend like Beckham.

Three miles from the sea the little river widens to two large spreadings; lochs in their own right on the map. And it's here that the trout rod you hauled up and over the mountain in its protective tube will hopefully bend like Beckham.

The quarry is salmon and sea trout - but the technique is trout fishing. In these wild and remote parts of the British Isles, salmon average between five and seven pounds. A 10-pounder is a good fish, any larger is a leviathan.

A calm day in the most outer of the Outer Hebrides is thankfully a rarity. Almost every day is a good day to hang out the washing. There's also a fair smattering of days when Force 12 on the Beaufort Scale just doesn't cut it. What I'm really trying to allude to is there's usually enough wind to put a hull-slapping wave on these two lochs and give your flies a jaunty wiggle.

The first of the two lochs is a weedy hole. It's mainly unfishable. Even if you whip off your dropper flies and leave the tail fly on, you'll probably still get snagged on weeds at every second retrieve. But at one end of this weedy loch, as it narrows before briefly becoming a river again, there's a deep peaty pot where salmon and sea trout congregate, porpoise, leap, play and generally hang out until a spate gees them out of this lower loch and further up the valley's waterways.

This pot or pool is of uncharted depth. It's deep, way too deep to wade and if you prod a rod into it you won't feel it touch the bottom. To add to the pool's allure, the water is normally heavily peat-stained. If you thrust your hand into it then it would disappear from view after about a foot. This is as murky a pool as I know and as dark as the inside of a cow.

But like most of the little salmon in the Hebrides, they can be tempted - by size 10 or 12 single hook trout flies. Camasunary Killer can be deadly here as the tail fly. Clan Chief on the top dropper would likely catch you a few sea trout. And all on a trout rod of around 10ft.

Because this pool is no larger than the average living room, the odds of hooking more than one salmon are less than Lord Lucan romping home at next year's Grand National on Shergar. Once hooked, a fish tends to career around the pool, somersault a few times, run up and down and generally do everything apart from what you want it to do - and that's come quietly to hand.

Every other salmon and sea trout in the pool - that may have been next on your hit list - has fled, is lying low, sulking or outright petrified. It's a rare day indeed that more than one salmon can be caught here. But, like most things in fishing, there is a workaround.

I've hooked three salmon from this pool, one cast after the other. I landed two of them by immediately applying plenty of sideways strain and walking them up into a less populated upper corner of the pool. Once there, further spurts of sideways pressure kept them there until they were ready to quietly come to hand.

My third fish, despite my previous successes, refused to be led - this time a bigger salmon and a rusty cock fish furious at being hookwinked after taking my deeply sunk Camasunary. One mighty backwards cartwheel from him and my flies recoiled towards me with the waves of his successful escape bid fanning around the pool like an atomic bomb at Bikini Atoll.

Fishing time way out here is always short because of the long and arduous trek to and from the valley.

Fishing time way out here is always short because of the long and arduous trek to and from the valley.

All hopes must now lie 100 yards away at the upper river spreading, a small loch with a big reputation where last season I saw seven salmon hooked, landed and returned by one angler, using a trout rod, in just two hours.

On the short walk to the second loch the river opens briefly again behind an ancient drumlin deposited an aeon ago. A few casts here can often pick up the odd surprise sea trout or if you're lucky a salmon.

Most puddles, burns and streamlets in the Outer Hebrides are worth a cast or three and shouldn't be overlooked - no matter how small. I've taken some monster 2lb-plus wild brown trout from black, peaty moor puddles no wider than a car.

This second loch though is the jewel in the crown. On the southern wind and rain-lashed shore is a well-documented salmon lie. It's here, among the jumble of rocks and tufts of broken heather banks, that most of the loch's fish congregate before pairing off. It's where the rusty, old residents mingle with the lively, fresh springers - a bit like attending a family party at your granny's old folk's home.

The shore here shelves off quickly and to fish the water properly without a boat means some deep wading beyond the lie so you can cast towards the shore where the salmon rest.

A few moments to catch your breath, survey the imminent weather - because weather is always imminent in Harris - and you'll probably hear and spot the splash of a salmon head-and-tailing to himself. Gently at first you wade, a few steps at a time as you pick your way through the boulder-strewn loch bed. The waves slap your back as you turn to face the shore, you peel line off your reel and there's a fish just under the surface. You see the bulge on the loch just between you and the white foam that's been whipped up by the wind and is now trapped on the shoreline.

Straight into a back cast you go and gently down floats the fly line on the forward cast - in front of where you think he's lying. Hunched forwards and coiled for the take, you slowly retrieve a yard of line. The Muddler now on the dropper popples seductively through the waves and the anticipation is electric. Nothing, absolutely nothing, else matters. Another yard of line and then bang! Except it isn't a bang, it's just how you later recount the savage take to your friends; a kind of explosion but without the noise.

Straight into a back cast you go and gently down floats the fly line on the forward cast - in front of where you think he's lying. Hunched forwards and coiled for the take, you slowly retrieve a yard of line. The Muddler now on the dropper popples seductively through the waves and the anticipation is electric. Nothing, absolutely nothing, else matters. Another yard of line and then bang! Except it isn't a bang, it's just how you later recount the savage take to your friends; a kind of explosion but without the noise.

The salmon, of about six pounds, hasn't been in the loch for long - maybe a few days. It's already starting to lose its bright and silvery sheen but it's lost none of its fight.

It took your tail fly, a faithful Camasunary. There was a sharp downwards yank and the fish was on, no God Save The Queen or delayed strike required. It just hooked itself. All you've got to do now is land this enraged salmon which is a bit like telling Neil Armstrong to just land his rocket on that there bit of moon, buddy.

Your knuckles take a dusting from the reel handle as you try to keep your rod tip up and regain your balance. Way out you half clock a fish jump clean out the water, except it's your fish and it's still attached to your fly. You reel in and it reels you out. You're never really in control until a salmon is on the bank and that's where you get him, eventually.

And so it goes. You return to the loch, wade out to your waist and fan cast your way along the shore hooking, landing and losing salmon.

At the end of the 30-yard lie, the shore takes a little detour to form a shallow bay where vast boulders disrupt the marching waves. It's here that my friend hooked almost a dozen salmon in two hours, landing around half that number. I sat and watched. What else can you do? He stood in the one position for the whole two hours fanning his casts and lengthening his line. I helped him tail the occasional double-figure salmon and we laughed together as fish after fish tore off with his flies.

When they're on, salmon are well and truly on.

When they're on, salmon are well and truly on.

Nothing, no matter how good, lasts forever. And out here time marches relentlessly on. Dusk fast approaches. We tackle down and shoulder our Bergens for the near-vertical ascent back out the valley.

At the top, on the ridge, you take a final look back. The two river spreadings lie far below, a pair of dog tags that reflect the red glow from the setting sun.

From up here you can't see the salmon leaping but you know they're there.

And that's good enough.